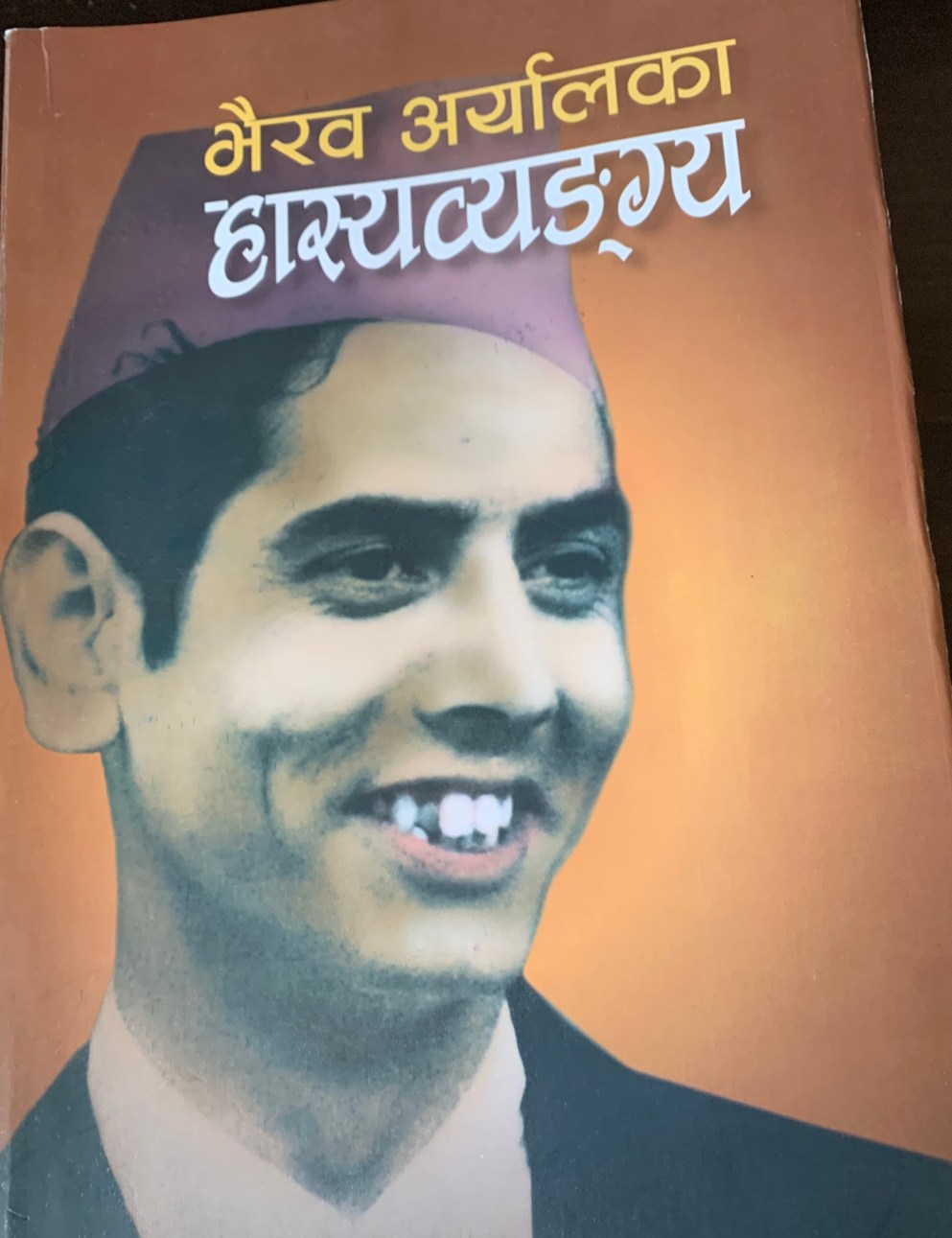

This is my translation of a famous Nepali literary essay ‘Jaya Voli’ written by master satirist Bhairav Aryal. This essay satirically exposes the stranglehold that procrastinating everything for tomorrow has in Nepali society. Aryal was a luminous light of Nepali literature, renowned for using his unparalleled gifts of humor, satire and irony to touch on some of the most quintessential aspects of Nepali society — good or bad. In high school, his essays were a part of our text books, so this essay was something I grew up with. On my most recent trip to Kathmandu, while discussing his works and this essay in particular with some cousins, an idea struck me that I should try and translate this famous essay into English.

Far as I know, this essay was published as part of an anthology called “Kaukuti” that came out in 1962. Kaukuti literally means tickle in English. It’s almost impossible to truly capture the way he plays with the words, particularly some onomatopoeic Nepali words. He uses such words skillfully to create sounds and cadence that are not only humorous by themselves but also sharpen the satirical edge of his sentences. Nevertheless, I have tried my best to find the right balance between literal translation of his words and capturing the essence of his ideas and anecdotes. If you were to derive even just a fraction of the enjoyment from reading this essay as I did from re-reading and translating it, I would consider this endeavor a success enough.

—

The day-after-tomorrow’s yesterday and yesterday’s day-after-tomorrow is called ‘Tomorrow’. In the eternal continuum of time, Tomorrow has this equally intimate relationship with both the past and the future. Perhaps that is why Tomorrow is far dearer to us Nepalis than Today. We live in our hopes for tomorrow, do our duty and want to preserve something for tomorrow before we die. Even when we are tired to our very bones, we go to sleep harboring all kinds of dreams for tomorrow. But, when we wake up, we find that Tomorrow has turned into Today. No matter, we run after another Tomorrow again. As we turn the pages of our calendar, Tomorrow keeps receding further and further, like a mirage, so near, yet so far, continually slipping past us into the future. And eventually, we meet our Maker before we meet Tomorrow. Tomorrow is thus like a God, whom Man is forever chasing and worshipping but just like God, it never appears in person, it is forever in sight, and yet never to be found. This gives Tomorrow a mystical quality that increases our worship of the deity that is Tomorrow. Like a religious man reciting god’s name, chanting ‘Tomorrow’ on every occasion is also a form of recital for us. To put off today’s work for tomorrow is our national heritage. And who among us dares to not follow our heritage, our custom!

In truth, perhaps the greatest quality of our Eastern philosophy is Tomorrow’ism — our worship of Tomorrow. Our philosophy teaches us to work hard today (while we are still alive) to find salvation tomorrow (in afterlife). But there is a major point of departure between this teaching and our practice. While our philosophy teaches us to work hard today to reap the rewards tomorrow, being intelligent humans, we don’t simply follow this instruction. Using our intelligence, we interpret that if the reward shall only come tomorrow, why do anything today, I might as well only do it tomorrow! And from this schism emerges our modern religion of ‘Tomorrow’ism’. And you and I, we are all ardent followers of this deity, our sacred Tomorrow.

When exactly did Tomorrow’ism start to take root in our Nepali society, it is hard to say. But my guess is that it started well before the time of even our very first poet, dear old Aadhikavi Bhanubhakta. He is supposed to have once said in exasperation, “Everyone’s been putting off giving me something, saying tomorrow, tomorrow; now someone, somewhere please give me a bag full of goodies, today.” It’s fortunate for us that the venerable old poet didn’t abscond to the woods in exasperation, off with his bag of goodies, saying, “To hell with care and nurture of Nepali literature”! From Bhanubhakta’s veiled threat, we can infer that the cult of Tomorrow’ism did not start with some saint or scholar like himself who set an example for the masses. Likelier, it was started by those who dole out injustices freely while dwelling in houses of justice. Some old judge, or a Colonel, a master aristocrat up on high, or their madams and mistresses. Or perhaps it could be one of those priests or pharmacists who held power over ordinary people desperate for their blessings or balms.

I remember my great grandfather once telling this story: In his village, a neighborhood house caught fire and started to burn down. Instantly, the landlord called the village chief. But the chief had gone to his in-laws’ place for a religious feast. So his wife promised, “I will tell him as soon as he comes back tomorrow.” The next day, that is tomorrow, first thing in the morning, even before he had finished his first batch of pipe tobacco, the chief went to the police station to inform them but turned out the station manager was off that day. So the chief was asked to come back tomorrow. The next day, the station informed their superiors, who the next day, informed theirs. From then, the missive moved up the chain of command, taking up its own share of ‘tomorrow’ at each successive step. Eventually the news made its way to the top, to the all-powerful his majesty, the Rana Prime Minister, a full three months and three days after the incident first occurred! At the moment of being informed, the Prime Minister was playing with his thirteen grandkids in the courtyard and barely registered the news and just mumbled, “Okay, remind me tomorrow.” The next day, when reminded while he was scenting his armpits with French perfume, he said, “Oh yeah, this was mentioned yesterday.” He commanded, “Have the fire extinguished urgently, tomorrow”!

Now, one may think that if only there were telephones around back then like these days, this type of situation would be avoided. But no, when Tomorrow’ism takes hold, not even the magic of telephones is enough to overcome its spell. For example, just the other day, a female relative of mine who was pregnant went into labor. In our grandmother’s time, they say the womenkind were strong and they could pop their newborns out like nothing, even while walking and going about their daily business. But these days, pregnant women tend to start groaning with pain two months in advance. Moreover, this relative of mine, it was her first time. So, we had no choice but to get her to a hospital. In order to get an ambulance, I went to my neighbor’s house and started speaking into the receiver only to find out that the line was totally dead. The receiver was just dangling there like a leafless branch on a tree, there was nothing to be heard from the other end. The neighbor explained the situation saying, “Yeah the phone line’s been dead for three days. Every day, I keep thinking oh I will fix it tomorrow so it’s not been done yet. Please come back and check tomorrow.” Barely surprised, off I went to the hospital.

At the hospital, a young pretty nurse took in all the details of my story and proceeded to say with a soft smile, “We don’t have a bed available today and my supervisor is also out, please come back tomorrow; in addition, the ambulance is also broken, its brakes need to be fixed, it should be fixed by tomorrow!” You see, what else could I do but nod in agreement. If only the neighbor’s telephone were working, I could have relayed all this over the phone to my pregnant relative and seen if she could postpone her delivery until tomorrow. But that was not an option, So, I lumbered my way back home expecting the worst, but luckily it turned out she had popped her baby out through the automatic channel, like in the old days! Otherwise..

With this example, you can see for yourself that even the most modern of inventions such as a telephone is helpless in overcoming the immense power that Tomorrow’ism has in our society. Scientists around the world are coming up with new inventions every day to speed things up. What someone says in the streets of New York can be heard in New Road; if someone types something in Paris, the print comes out in Kathmandu. But none of this has any effect in shaking off the spell that Tomorrow’ism has cast over us. That’s why I have always called Singhadurbar, our old palace and now the house of parliament, ‘The Palace of Tomorrow’. Because wherever you go there, no matter which floor, which room, which desk or corner, you will find ‘Tomorrow’ waiting to greet you everywhere. Whether you are looking for a job or just an appointment, everything there is reserved for tomorrow. It’s very rare to find a government office in our land that is not inflicted with Tomorrow’ism. It’s almost as rare as finding a Brahmin who has managed to stay a vegetarian in this day and age.

It’s not just the public sector, the private sector is inflicted just as bad. Someone borrows five hundred rupees from you promising to return it tomorrow, but it remains unpaid for five hundred tomorrows. The shopkeepers in town may keep pointing to a sign in their stores that says ‘Cash Today, Credit Tomorrow’, but it’s impossible for them to run their business without selling on credit. For the customer however, tomorrow never comes. It takes more than fifty tomorrows for a person to pay fifty rupees to his housemaid. A well-wisher puts off a small favor that would take less than three minutes, keeps you waiting every morning at a stinky town square for three months, where he never appears, only Tomorrow does. You go to a money-lender for a loan, he says Tomorrow! You ask a writer about his article, he also says Tomorrow! The clerk at the court says tomorrow for your appointment, the accountant says tomorrow for your salary. It’s him, her, everyone, the tailor, the janitor, the plumber. Tomorrow’ism has long seeped inside our houses and marriages too. Even husbands and wives keep each other waiting, with the use of good old Tomorrow. When the husband politely requests that the wife wash his hat, she says I will do it tomorrow and doesn’t get to it for a week! And similarly when the wife tells her husband that she is running out of salt in the kitchen, he also keeps saying I will bring it tomorrow, for a week.

In this milieu, where everything is drenched with Tomorrow’ism, it’s no surprise that our default mindset is to put everything off for tomorrow. Truthfully, not only do we keep fooling others with Tomorrow’ism, we also keep deluding and coddling our self esteem with the false hope of Tomorrow’ism. Have to study? Will study tomorrow; have to visit someone? I will go tomorrow; this task or the other? will do it tomorrow. In the same vein, some children, wary of going out in the cold of the night, even put off going to the toilet and save their natural business for tomorrow.

The only notable exception to our default setting of Tomorrow applies to food and eating. No one waits until tomorrow to eat. We think if we let the food be overnight, it may become stale and stinky, inedible and go to waste. To illustrate this exception, let me relate a recent incident. There was a big buffet dinner being served for a party at Shankar Hotel in Lainchour a couple of months ago. And at the party was this military Colonel, an acquaintance of mine, who didn’t go to parties that often but it seemed he had made sure he came to this one, just for the buffet. When I saw how much this guy was eating and drinking, I was astounded. He must have eaten an amount that could have easily been enough for half a dozen people. Eventually to make some small talk and also to cure my curiosity, I teased him gently, “Careful Sir, you may not feel so well afterwards.” He retorted, “Oh well, in that case, I will just take some medicine tomorrow!” From his simple yet profound answer, we can conclude that we Nepalis follow Tomorrow’ism to a tee for everything but eating. This is also our national trait.

Except for eating, all our other affairs and activities are steeped in Tomorrow’ism. Tomorrow’ism is our culture, it’s our philosophy, our politics, our administration and it is our most distinguishing social custom. In my feeble mind, I worry if this habit of procrastinating everything off for tomorrow will lead to our ultimate ruin; if we will beggar ourselves and be condemned to take to the streets or to the woods, just like Bhanubhakta warned. It’s not impossible! Just as we put off today’s work for tomorrow, this habit could easily extend to putting off this year’s work for next year, this decade’s for the next decade. Maybe all responsibilities of the twentieth century will be reserved for the twenty first century. Let’s just hope that the planets and the stars don’t start mimicking us in our procrastination. What if the Earth were to decide to rotate tomorrow and rest today; what if the Sun decides to not rise today and save its exertion for tomorrow. Heil Nepal! Heil Tomorrow’ism!