Back in April 2013, I visited the Killing Fields and Tuol Sleng prison in Phnom Penh Cambodia. These sites exhibit the genocide that the Khmer Rouge committed in the 1970’s against their own people, driven by a violent, extremist communist ideology. This visit was my first and only encounter (even so far) with a genocidal site and tragedy. I was pretty shaken up and overwhelmed by the visit. I had to sit down and jot something down over an afternoon in my hotel to find some release. Coincidentally, it was the first of May, May Day. I am sharing this here now, with some copy editing done to what I had written then.

I did not get a chance to tour the Killing Fields and the S-21 Tuol Sleng prison during my first visit to Cambodia last November. I did so this past weekend. Just like humans, countries need to embrace their dark sides, it may not always be pretty, but it is an important part of their story, their people. I admire the Cambodian people and the government for their courage and sense of responsibility in exhibiting the darkest period of their history, a period when almost half of its eight million people were killed brutally by the Khmer Rouge, the communist revolutionaries.

When I visited in November, I chose to spend the only spare weekend I had in Siem Reap, visiting magnificent ancient temples built during the Angkor Empire. Afterwards, while waiting for my flight to Bangkok en route to visit my family in Kathmandu, I picked up this book at the airport called The Gate. The Gate is written was by a Frenchman named Francois Bizot, an ethnologist who had been traveling around Cambodia researching Budhhist customs in rural provinces. When the Khmer Rouge revolution broke out in the 1970s, he was taken prisoner by the Rouge and detained along with other Cambodians who were also taken in en masse and held in prisons and torture camps around the country. Bizot was directly supervised by a Khmer Rogue commander named Duch, who would go on to become the head of the Tuol Sleng prison, a school in the middle of Phnom Penh city that was later turned into a prison. At this prison, vast swathes of Cambodian urban middle class were detained and tortured before being transported by trucks to the Killing Fields, which lies only about twenty kilometers southwest of the Capital. In the Killing Fields, the prisoners were executed heartlessly and buried in graves, usually at night.

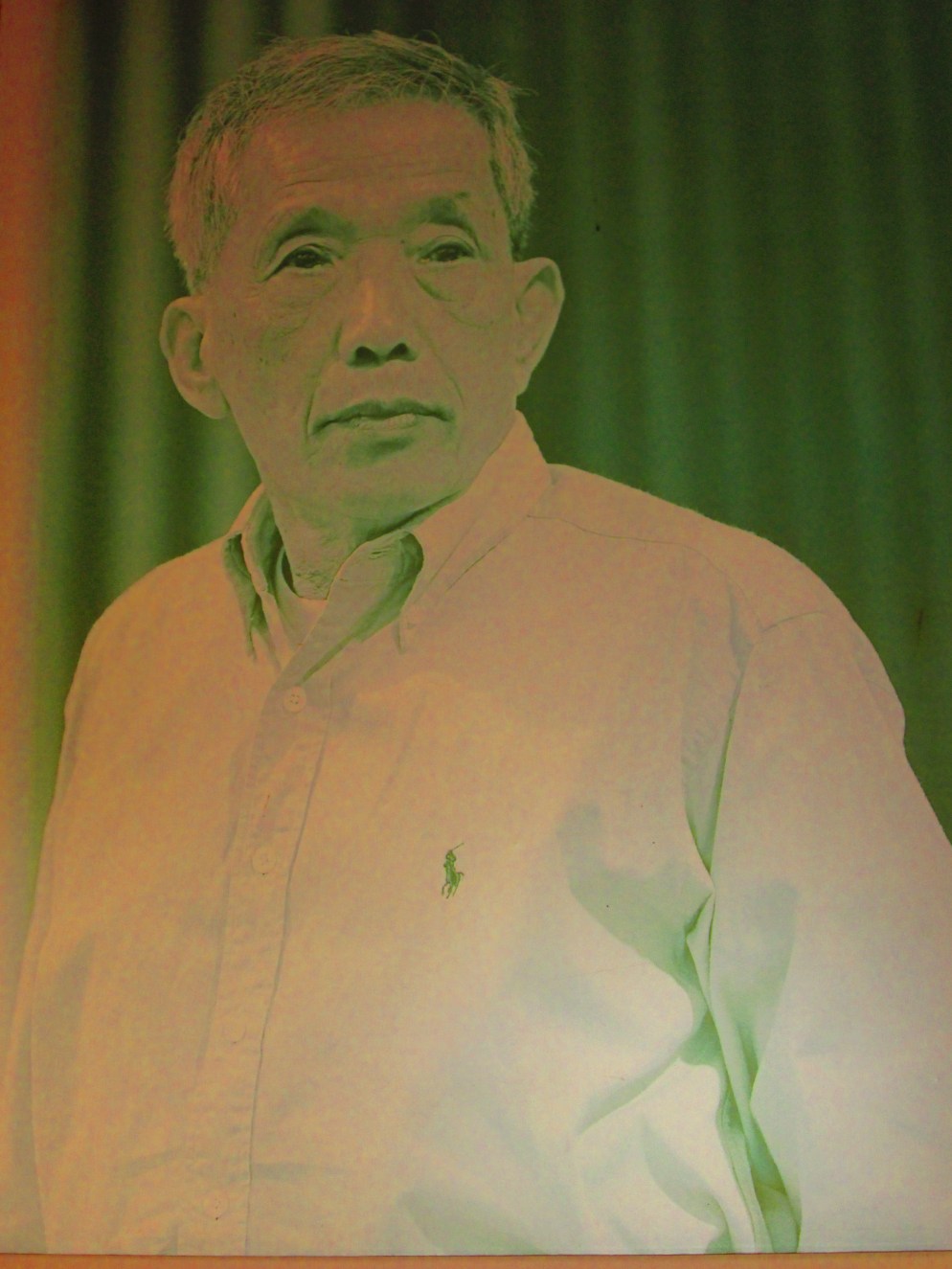

Duch was later discovered in the late nineties I believe while living incognito in a rural village by a foreign researcher who was traveling in the provinces to learn and document the experience of the local people who survived the horrible tragedy. This news of Duch’s discovery and arrest prompted Bizot to write The Gate where he describes his experience during detention and eventual release by the Rouge. He relates the sense of helplessness that engulfed him as he witnessed waves of senseless murder sweep over the idyllic, tropical landscapes he had grown to love. He is conflicted as to whether he was lucky to survive or unlucky to live on with a heavy sense of guilt towards the souls of many of his Khmer friends who were not so fortunate to escape. It is a beautifully written book, authentic and honest. One of the things that stuck with me from the book was Bizot’s description of Duch as looking very plain, innocuous and ordinary in the pictures released after his capture. Duch was a former math teacher who inspired by the Khmer Rouge’s revolutionary ideology committed mass murder against his own people with the most unfathomable cruelty and efficiency.

As I walked around the various sites and monuments around the Killing Fields, it was amazing to me how ordinary of a setting it was. Cows grazed on green fields, flanked by rice paddies against a background of buildings and skyscrapers in Phnom Penh city; hens frolicked around gaily; a small, still, lake lay in the middle surrounded by pits. But these pits were turned into mass graves. There were lush green trees and orchards where people were hanged; thick, ridged barks against whom, people, women and children mainly, were beaten to death. There was one tree in particular with long, pointy leaves and sharp, scaly ridge-like barks. These ridges were used to slay thousands of people, as after a point, the inrush of inmates was getting far too large to kill them all at night at once.

There were several visitors, mostly foreigners, who were doing the tour of the sites but I don’t think I heard a single conversation during the two hours I spent there. People were absorbed reading the memorial signs, listening carefully to the audio guide, quietly gazing into the distance, taking photographs and some probably tearing up behind the shades of their sunglasses. It was a hot sticky afternoon, the sun blazed in unashamed vigor well into the late afternoon. I had not eaten since breakfast, but I felt no hunger whatsoever. I smoked a few cigarettes quietly sitting on a bench on an artificial conservatory dyke built around the lake to preserve the remains of victims’ graves against flooding. The lake was still and green, I wondered how many wails of death and sheer terror it had quietly absorbed forty years ago. I tried to imagine coming to the Killing Fields alone on a moonlit night, I was so frightened at the idea, I silently, abruptly quashed my imagination down in the lake in front of me.

At the end of the tour, I stepped briefly inside the memorial museum where there were several pictures and documentations of Duch’s sordid cruelty. As horrible as everything else I had witnessed was, it was the enlarged portrait of Duch, that probably disturbed me the most. He looked just as Bizot had described, an ordinary old gentleman, with slightly wrinkled face and sunken features, greying hair, but looking pretty healthy and at peace with himself, a hint of a gentle smile at the edges of his lips. His eyes were almost kind, his posture, avuncular. His picture reminded me how gently and harmlessly evil could be clothed. Through the course of our daily lives, in professional and personal settings, we often read into people’s features and body languages, we make judgments of their character based on our impression of their looks, the way they walk and the way they look at you, what we see in their eyes. We make far-reaching decisions based on these observations and perceptions. Duch’s portrait was a stark reminder of how horribly and easily, we could misjudge these things. Not necessarily because we are deceiving ourselves. But because of how important a role conditioning and environment play in how people turn out later, how their conscience is shaped, what actions they take.

I read and finished The Gate during my stay in Kathmandu back in November, often in an outdoor café in late mornings, enjoying the gentle warmth of the winter sunshine in Kathmandu. During those mornings, even as the sun soothed me physically, I often thought how violently and dangerously a fire fueled by a grand ideology, a sheer unwavering belief in something, Truth with the capital T can burn. Those thoughts came rushing back to me again as I stood there in the museum for several moments gazing into Duch’s eyes. I left the museum, relieved myself without closing the toilet door, washed my face with water from the water bottle I had bought earlier. Before leaving the site, I went and wrote down some reflections on the visitors’ memorial book. I was quite overwhelmed. My heart pained for all those that had been killed and tortured in those lush, green fields. They were also with those who had somehow escaped and survived the tragedy. I wondered how many of those who survived think whether they were lucky to survive or unlucky to carry the pain of memories somewhere deep inside them. Like Bizot.

On the way back to Phnom Penh, it started raining quite heavily. I sat in the back of a Tuktuk just looking at the rain and listening to its sound, trying to completely vacate my mind of any thoughts, savoring the smell of fresh rain pouring over the dirt. The tuktuk driver asked me if I would like the cover pulled down to keep out the rain. I said no. I wanted to feel the splashes of the fresh rain against my parched skin. I eased into a sensation of the previous two hours dissolving away in the rain, melding into the hustle and bustle of the early evening city life, the quiet commotion of people talking and sitting outside in bazaars and shops lining up the streets that led back to Phnom Penh. The next day, I went to the Tuol Sleng prison, formerly a school right in the middle of the city. In some ways, this visit was even more painful as many rooms there still carried bloodstains and marks that spoke of the torture meted out by Duch and his people. I wondered how many of the prisoners held there had an inkling of the fate that awaited them in the pastoral fields that were only about an hour away.